Charitable giving may be something that you grew up with, a value passed down by your parents or a practice encouraged by your religion or culture. Philanthropy also may be something that you have come to believe is important over the years, especially if you are fortunate enough to have amassed “enough” for your and your family’s needs and even more so if you had help along the way.

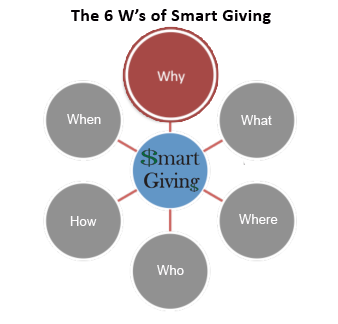

Each of us has our own story and aspirations, and will have a different answer to the question “Why do I want to give?” In studying donors, however, we’ve come to see that there are four sets of motivations that can explain most giving decisions: achievement, significance, legacy and happiness.

Each of us has our own story and aspirations, and will have a different answer to the question “Why do I want to give?” In studying donors, however, we’ve come to see that there are four sets of motivations that can explain most giving decisions: achievement, significance, legacy and happiness.

We’ll use National Public Radio (NPR) donors as a case study. NPR donors have one important thing in common; they listen to public radio. But why did they choose to part with their hard-earned cash in support of NPR?

Some people were motivated by a sense of achievement, but that meant different things to different people. Some people got a lot of satisfaction from an on-air mention during phone-a-thons, and would wear a giveaway NPR t-shirt with pride. Others liked having their name published on a major donor list.

Others felt a sense of accomplishment from what they learned by listening to NPR. Still others were drawn by the opportunity to lead a fundraising team, or serve on the board. And some were eager to get an invitation to NPR events.

(Examples abound among other donor groups as well. Educational institutions count on the loyalty of alumni, and class competitions are a common fundraising ploy. Some non-ballet lovers will support the local ballet in order to gain social access or acceptance.)

Some NPR donors gave so that they could be of significance and have a positive impact on someone or something they cared about. They felt obligated to provide intellectually honest news and noncommercial cultural content to the nation, and thereby support an informed public debate.

(People also will respond to urgent needs. Dire circumstances brought about by some sort of catastrophe, in particular can motivate people to step up, as evidenced by outpourings of support after the devastating earthquake in Haiti or Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.)

Some people were inspired by the desire to do something that will matter when they were gone, to leave a legacy. NPR offered an opportunity to sustain a type of information and cultural experience that they valued, and felt others should be exposed to.

Joan Kroc is a good example. She believed in the power of public radio, and had enjoyed NPR programming over the years. As she began to plan her bequests, she approached NPR regarding a gift. NPR executives were startled—and understandably delighted.

Extensive due diligence was required to satisfy Joan that her gift would be well managed and her intentions honored. NPR evidently passed the hurdles. When Joan died in 2003, NPR received more than$200 million, and an additional $5 million went to a member station in San Diego.

Last but not least, there is happiness.

For some NPR donors, it was about the feeling of being “among friends” in the virtual community of the airwaves. Tuning in to NPR while making the morning coffee or driving to work was a familiar part of their routine and “Guess what I heard on NPR!” was a great conversation starter.

(Most donors just plain feel good when they give. What some call payback and others call gratitude can be a factor; many scholarship students later return the favor. Sometimes the giving experience can be downright fun; witness the huge success of the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge.)

So, why do you want to give?

The answer may be some combination of the four motivations, and may depend on the giving opportunity or the amount of money (or time) you are thinking of giving. “Checkbook” gifts are very different from something that represents a major portion of your philanthropy.

Our research shows that checkbook gifts often reflect a passing interest or a quid pro quo (your friend gives to your cause, so you reciprocate). You may make a lot of them but they represent only 5-15% of your giving.

Something that is a personal priority – have you asked yourself, “What problem do I want to solve?” – is likely to garner a more significant portion of your dollars and time. And a true passion – like finding a cure for a loved one’s disease – can lead you to devote a major part of your philanthropy to one project.

Timing is a factor too. When you’re starting out, you may have more time than money, and contribute through volunteer work. The young bucks are more often motivated by achievement, while those in their later years are thinking about legacy.

“What do I hope to accomplish?” is another good question, closely followed by “Do my means match my ambitions?”

Finding a cure for cancer may be your passion; there are many ways to help. A few people can fund a major drug discovery and development initiative; more can build a wonderful, peaceful garden at a cancer treatment facility; and many show up to participate in walkathons.

Giving is an intensely personal act. Take the time to think through why you want to give, and you are more likely to feel good about the good you are doing in the world.