If this looks like your planning process, you are – unfortunately – not alone.

“Failing to plan is planning to fail.”

That adage, with some variations, is attributed to both Winston Churchill and Benjamin Franklin. General Eisenhower added: “Plans are nothing, planning is everything.” We agree that planning really is more about the process than the output.

Fundraising planning is not magic. Or rocket science. And, there is no such thing as a perfect plan, because things will change. “A good plan today is better than a perfect plan tomorrow” is another wise saying.

Finally, a reminder: fundraising planning does not – or rather, should not – occur in a vacuum. It is part of a whole system approach to fundraising that we introduced several months ago in a blog titled “The Big Picture.“

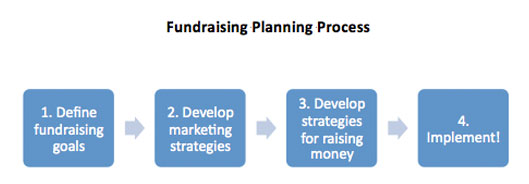

In the sections below, we’ll briefly walk through the steps involved in developing a comprehensive fundraising strategy with a unifying marketing message, and being disciplined and flexible in its implementation.

Step 1. Define fundraising goals

It starts with entity planning: defining your mission, determining your resources requirements, developing your economic model, and identifying financial sources and gaps. The question then becomes: how can fundraising help?

That said, the reality is that there is a back-and-forth relationship between entity and fundraising planning. Some entity financial needs may not be achievable through fundraising; operating expenses are notoriously tough to “sell” to donors. On the brighter side, unanticipated gifts may arise; someone sells a business or decides to do an estate plan, and gives you a call.

Ideally, senior Development staff is engaged with other leadership in entity planning discussions. The goal is agreement on an overall fundraising target figure, and a list of major fundraising initiatives. You want to be ambitious but realistic, which requires a series of questions:

- What strategic initiatives or operational needs would be attractive to donors?

- How much do we reasonably expect to be able to raise, for each targeted initiative?

- What is the most likely source of funding – grants, individuals, corporations, government?

Next, how to make your “pitch”? Fundraising – never forget – is about selling, and everyone in the organization is a fundraiser.

Step 2. Develop marketing strategies

The goal is a powerful and cohesive marketing campaign that supports your fundraising efforts and resonates with target audiences. Developing and delivering it is a team effort. The basic tasks are:

- Develop your key messages. A cascading approach can be powerful. Start with an overall story and themes that are clearly linked to your organization’s mission. With that as the umbrella, develop a theme for each initiative and/or funding source.

- Build a high-level communications program. That will require assessing your target audiences (i.e., funding sources), identifying communication channels, and designing marketing materials. Equally important: training fundraisers on the use of marketing tools.

In “The Art of Simple Nonprofit Communications”, we stressed the importance of addressing the needs of both internal and external audiences, with integrated but focused plans.

The internal communications plan is for “everyone” involved in your institution. This includes all staff and board members who have been or will be involved in fundraising as well as ambassadors, planning team members, volunteers, and other engaged stakeholders. General staff awareness also is important because, as we’ve said more than once, everyone is a fundraiser!

An internal communications strategy for institutional advancement is a core effort that should be led by a senior manager. He or she will advance the planning efforts, working with staff groups as needed to leverage the organization’s communications vehicles (e.g., email, in-house newsletters) and keep all stakeholders apprised of the fundraising effort’s goals and overall progress.

The external communication plan is for individuals, foundations, business leaders, educators, community leaders, policymakers, media and others who might be interested in learning more about your work and/or will be invited to join the journey with you. Public relations and press-oriented activities can complement targeted marketing activities.

Step 3. Develop strategies for raising money

Institutions’ targeted funding sources (e.g., foundation grants, corporations, individuals) will vary, depending on the outcome of Step 1. Strategies for each source must be developed and coordinated. We will limit ourselves, here, to some suggestions for individual giving strategy development.

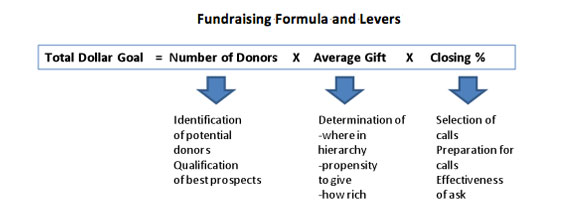

The best starting point, in our experience, is the “magic” formula for achieving your fundraising goal:

You can use the formula to test actionable options, each of which will have implications for both fundraising effectiveness and efficiency. For example, if you can increase the average gift size and/or your closing rate, you will need fewer donors to hit your dollar goal, which will reduce the workload for fundraising staff and volunteers.

Next, you can use the gift pyramid… but not in the traditional way, as an iron law of market segmentation that essentially reflects wealth distribution, with 80% of dollars coming from the top, 10% from the next 10%, and 10% from the remaining 80%. There are few problems with that.

For one, you can get so focused on averages that you fail to see the outliers. Have you heard the one about the statistician who drowned in a lake with an average depth of six inches? Averages conceal a lot. The average wealth of you, me and Bill Gates is not very useful.

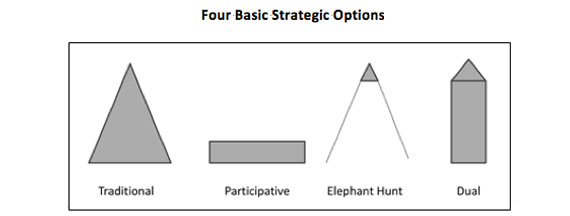

For another, the shape of your “pyramid” should look different depending on your fundraising strategy. A traditional triangle may make sense for an academic institution with a broad alumni base. But some institutions don’t have that luxury; their cause may be a priority for very few, if any, donors.

There are many fundraising strategies beyond the traditional pyramid, including the three shown below: participative (where you want everyone to give at least something), elephant hunt (where you’re after one or a few passionate supporters, as with many health-care initiatives), and dual strategies (which are common in membership organizations raising money for large projects).

Step 4: Implement!

There’s a lot of basic project management work involved in implementing any strategy. Strategy needs to be translated into action plans with tasks, deliverables and due dates, and then make sure it happens. Progress against goals and targets needs to be monitored, and reported.

When it comes to significant giving, one of the most important questions is: who to include in your “getting to giving” efforts?

Even with development staff and a corps of volunteers, there are limits to your fundraising capacity. How much time do your “askers” have available? What roles can or should they play? For a major fundraising thrust – such as a capital campaign – you may need to add capacity.

Targeting prospects is the other side of the coin. That will be more or less difficult, depending on your organization and strategy. Identifying and qualifying people who can make bigger gifts, however, is a challenge and opportunity across the board. Here are a few tips.

Start with “believers” who have given before, and use them to recruit other like-minded individuals. Leverage relationships; you know the person, or you know someone who knows him, or people in your organization know him. A warning here, though: don’t just sit around the table picking the brains of your board members, or you’ll just get a list of the usual suspects.

Another warning: making a list of rich people isn’t the answer. It’s not hard to find rich people; the trick is finding the right people. Who are natural allies? What are their board involvements, their giving histories, their financial circumstances, even their personal interests? That information is available, with some work.

You need to build a database of qualified prospects, including their potential for giving. You also have to consider their readiness for making a large gift. What stage of life are they in? (Many big gifts are still bequests or near bequests.) Have they experienced a major transition? (That entrepreneur who just sold his business may be ripe.)

None of this is a cookie cutter solution, of course. You will be learning as you go. Maybe that great idea for an event just didn’t work. Maybe you discover that you are more interesting to venture philanthropists than you expected. The one thing you can count on is that there will be surprises – some good, some bad. Be disciplined but flexible.

Oh, and have fun!